Imagine a town that grew overnight to a population of seven thousand—and for a moment in time (1876 to 1883) vied with San Francisco and Sacramento to be the largest city in California.

The heyday of Bodie, California lasted half a decade.

Today, the ghosts of this forgotten place, tell a story for current times.

The headstones of the celebrated people of Bodie–about two dozen- are clustered within a small fenced square on a weather exposed plateau, 8,300 feet above sea level. Those less celebrated Bodie, are buried outside of the fence: gunfighters, gamblers, opium addicts, and many of the seven hundred sporting women that worked their trade in the more than fifty saloons that lined Main Street.

Missing altogether is the tombstone of William Body, the town’s namesake.

He was lucky for a moment and struck his pick ax upon Gold, but froze to death a week later in a blizzard. Luckless even in death, his name was changed by a careless sign painter. The townspeople recognized the error, but preferred the new spelling: B-O-D-I-E.

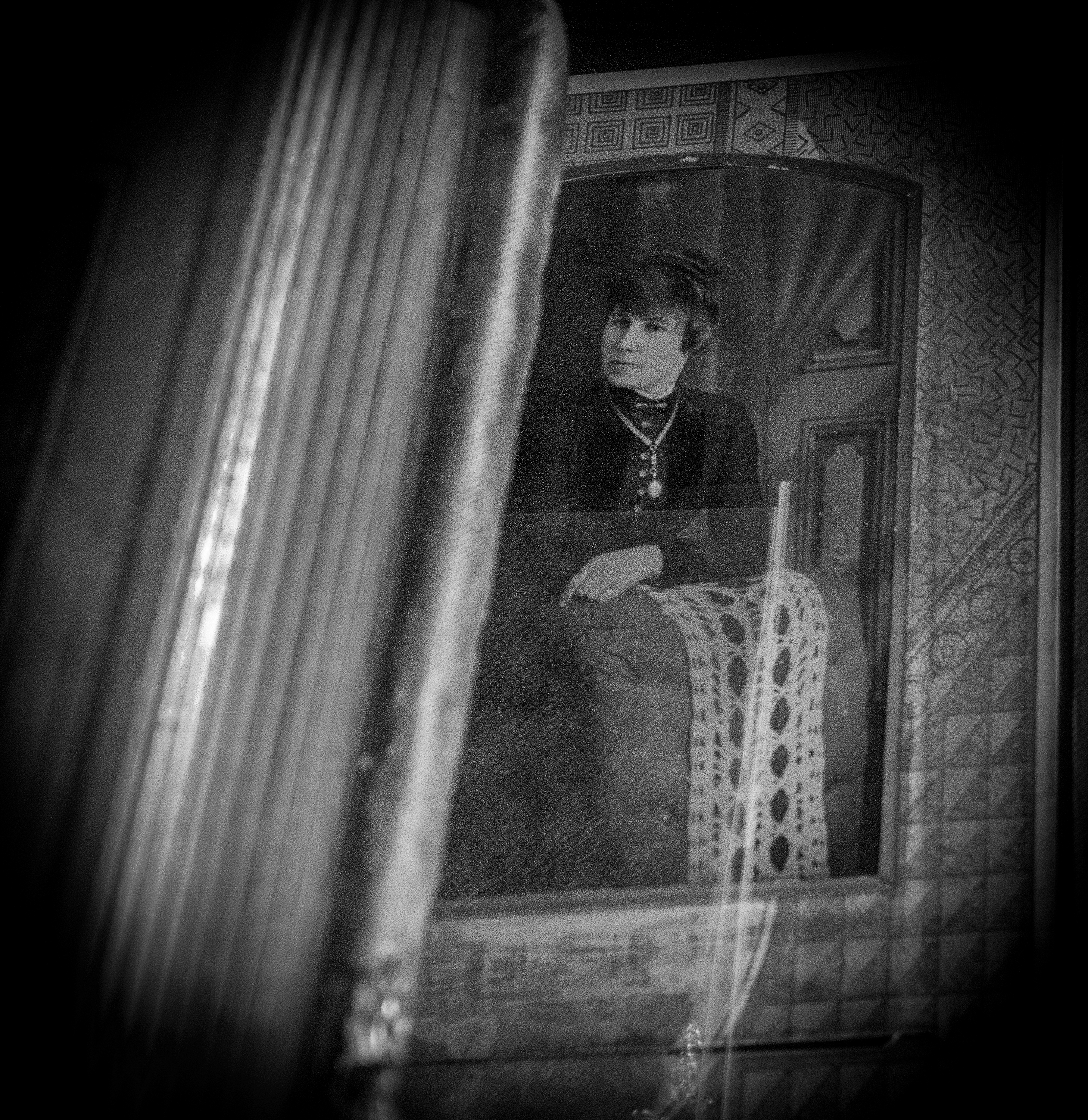

As I stood in the afternoon breeze surveying the headstones, some with full names, another with just a first name, “Lottie” , woman appeared next to me.

She asked if she could show me the town.

She introduced herself as Lottie, and pointed to the simple stone in front of us. ” I fit a lifetime of experience into those 35 years,” she noted.

This wise young ghost became my tour guide to Bodie. Together we strode down “boot hill” to learn what made and destroyed the town of Bodie.

Below us was a valley of green and yellow grass dotted with a cluster of long abandoned homes and places of business.

“Only 170 of the more than 2,000 structures remain,” explained Lottie. A church spire, a firehouse’s bell tower and a few barns lie exposed to the unrelenting wind. Most of the structures leaned over at odd angles. Parched grasses and purple mountain flowers overgrew abandoned wells, farm tools and wagon wheels left out in the open.

“This is Main Street,” Lottie said to me in a manner both business like and slightly flirtatious.

Her descriptions were concise.

“Saloons, general merchandise store, hotels, the miner’s

Union Hall, and two churches—one Protestant and one Catholic.

I don’t remember going to them in my time, “ She winked at me at that last remark.

She was dressed with immaculate detail. “The most expensive clothes available in San Francisco,” she replied at my stare.

I pressed my face into darkened windows.

The thick, handmade glass was fogged and warped from a century of summers and winters.

Lace curtains, oil lamps, and empty liquor bottles reflected back the sunlight.

Lottie spoke to my unconscious.

“In the winter, we dug a tunnel under twelve feet of snow to get from one side of Main Street to the next. That’s why we built homes closely together. None of us had seen winters so harsh—no matter what part of the world we came from. The only happy times here were in summer—when you could stand on this porch and watch the dust clouds beyond the hills turned into a twenty horse stagecoach coming to collect our gold.”

In my head, I could imagine dirt streets bustling with townsfolk, each with a separate purpose.

Lottie continued, “Miners came from New York, Boston, Philadelphia. The rich ones took a steamer through the Panama Canal. The boat captains were just as fevered by the gold, and abandoned their ships anchored in San Francisco Bay.”

“Just as many men came from Europe—mostly Irish, like you, she laughed.

I turned my head up the street.

“That was Chinatown”. Lottie told me. “The Chinese, Mexican

or Native Indians weren’t allowed to live near Main Street. The Chinese sold vegetables, did laundry

and operated opium dens with bunks for those who

preferred to smoke and dream.

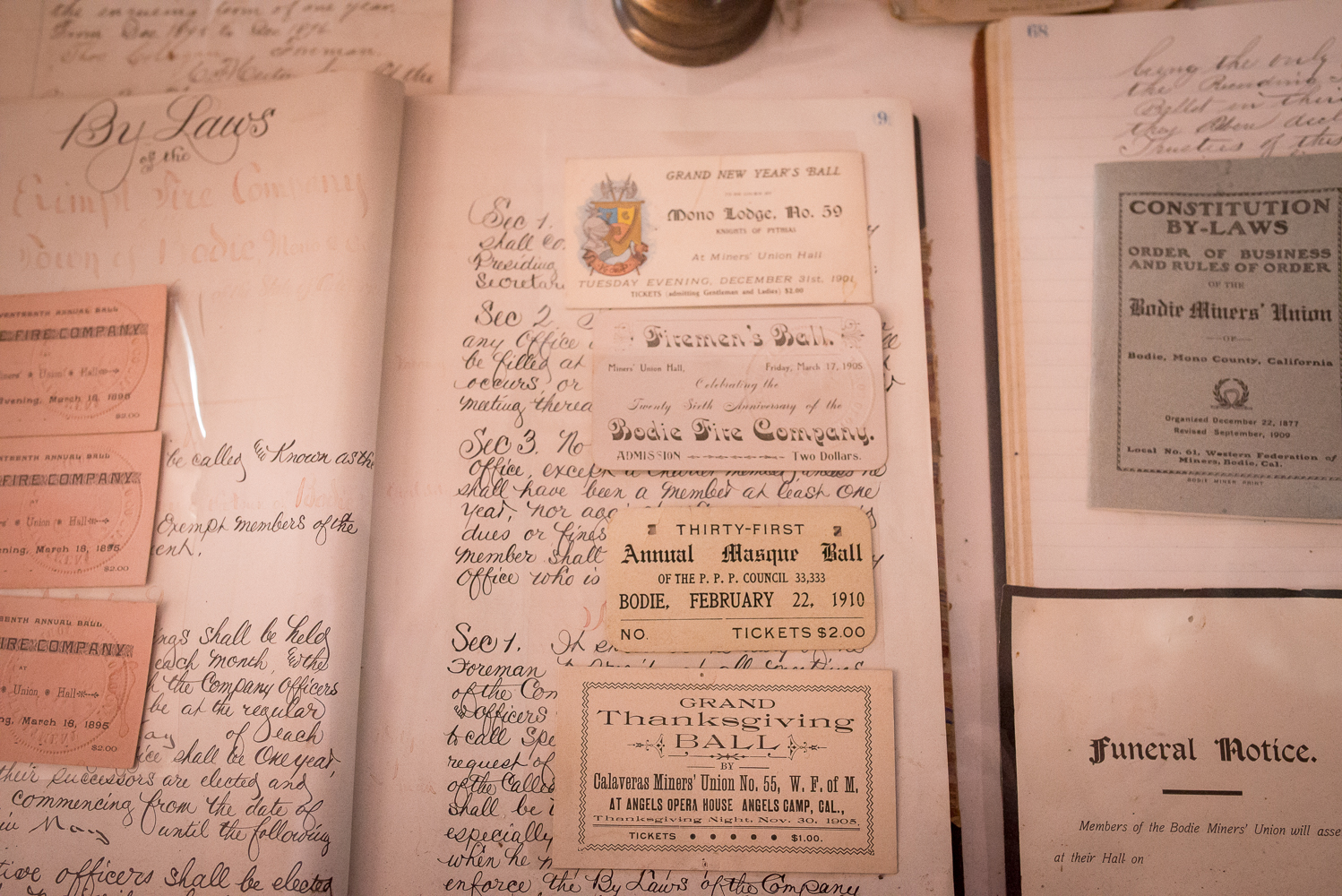

I climbed the steps and entered the Bodie Miner’s Union Hall. I thought I heard music and dancing. “We celebrated each gold strike,”Lottie read my mind and gave me the details.

“At first, a good man could make living himself swinging an ax, diggingthe ground, and sift through rubble for gold.

I touched a glass case protecting a sepia toned print of well dressed men.

Lottie continued, “Soon, however, a man working alone could no longer compete with newly formed companies of investors with better equipment. The mining companies bribed officials for the rights to the best claims. Disputes were settled with bullets. The law favored those with money.”

“In my profession, I had to be a good listener. I heard the stories of travelers, politicians, cowpokes, gunfighters, con men and husbands. I learned the news before it was written in Bodie’s weekly paper.”

I pointed to the displays of weapons.

“Dodge City had marshals who collected guns from cowboys entering the city. Bodie, instead, had a murder a day. Everyone carried pistols, store clerks carried shotguns, and the Wells Fargo driver carried “the messenger”—a man with a gun that fired many rounds in succession at a force that could cut the torso of a potential bandit clean in half. Guns kept everyone on edge. But ultimately, it was laziness not violence or greed that did us in.

The implications of Lottie’s insight drew me outdoors.

The tourists couldn’t hear Lottie, but I could.

“In five years, nine mines had shipped $34 million dollars of ore by stage through Aurora to Carson City and San Francisco–where the gold was minted into coinage.”

All the trees were cut down for railroad ties.

” A chemist was brought in mercury and arsenic in order to extract every last grain of gold dust from the waste piles. He discovered that a combination of mercury and arsenic did the trick. on another few years toxic chemicals were washed into the earth and the crops failed.

I walked past the rusted chassie of a pre-WWII automobile lying beside the wooden remains of an authentic Conestoga wagon.

“I saw the future coming” whispered Lottie.

“Remember I said, men loved to tell me their secrets? The top man at the mine said he invested his wealth in a San Francisco hotel and restaurants. People need to eat, and people need a place to sleep he told me. That’s more valuable than gold, he said. I wasn’t rich, but I was smart enough to hide the coins, gold shavings and jewelry I was given. I hid them in goods I sent to San Francisco—a little at a time —so as to not to draw anyone’s attention.”

She gave me a wicked smile. I could see how so many had been smitten with this beautiful yet practical ghost. I took a close look into the window of the once bustling Barber Shop.

“Lottie, One last question,” I implored. “How did it end?”

As I spoke, I saw more ghosts inside—the barber giving a shave and customers debating local politics. They noticed me too, and turned to give me the thousand yard stare.

Lottie translated their unspoken sorrow.

“I showed you how the town was crowded with wooden homes, barns, saloons and carts. Three fire stations were built and we even had trained fire volunteers. But no one bothered to maintain the water water reserves–we were too busy finding gold! See the buckets lined up and the fire bell across the street?”

I nodded my head then noticed a water pipe and its valve sticking out through the brittle sage and for some reason felt compelled to take a picture.

“A young boy, playing with matches, began a stable fire. The flames jumped easily from place to place. In the chaos.

“The the fire bell bell rang and rang,” said Lottie, “but there was no water for the hoses.”

I thanked Lottie for the tour she gave me, and asked her if she wanted me to walk her back to her grave.

“No, these days I prefer to walk alone,” she said with a smile.

Before her figure vanished in the way that all apparitions, mirages and dreams always do, she turned and gave me a friendly warning.

“Life is simple really. Gold is temporary. So are towns. People are the same the world over. All we really require are food to eat and shelter from storms. We can choose to live honestly and comfort others. Or we can choose to lie, steal and kill. But, when you kill your neighbor and you kill the earth around you, you speed your own demise. Not until your are a ghost yourself, do you see the truth so clearly: guns, opium, liquor, hate, vanity and yes, gold—are detours from happiness. Death comes sooner than you want. Your former neighbors may decide which side of the cemetery fence you are buried on, but they are not the judge that matters. You are.”

Lottie was gone. I walked the steep hill back to my car, and allowed my thoughts to return to the present moment.

Today , the town of Bodie is preserved by the State of California as Bodie State Historic Park.

If you decide to visit, you can drive into the park from May to October. In Winter the climate is too harsh for most, and the roads are impassable. The stagecoaches and railroad disappeared along with the gold.

The Author, Bob Gibson leads photography workshops at Bodie National Park each summer. For information email Bob Gibson at rjg@rjgibson.com or visit photomastersworkshops.com